Thomas Sankara: The Dead who Refuses to Die

“While revolutionaries and individuals can be murdered, you cannot kill ideas.” – Thomas Sankara

“For nothing is hidden which will not become manifest, nor secret which shall not be known and come to light.” – Luke 8:17

In Burkina Faso, like in many African cultures, it is believed that the soul of a murdered person will not transit into the “land beyond” until the crime has been atoned for or avenged. In some cases, it is even a belief that, if the killers do not confess their deadly acts or seek forgiveness, the dead will be regularly sighted around the homestead, the village square, marketplaces, etc. thereby prolonging the anguish of loved ones and disturbing everybody’s peace, including that of the presumed murderer(s). Hence, there will be no closure.

Almost thirty-five years after his death on October 15, 1987, in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 14 defendants, including former President Blaise Compaoré, were found guilty, on April 6, 2022, of assassinating Captain Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara, a charismatic and transformational leader.

Following this verdict, albeit in absentia for two key accused including former President Compaoré, would Thomas Sankara’s soul transit into the land beyond? Would his homestead know peace, more so that Compaoré has sent emissaries, including his daughter, from his exile in Cote d’Ivoire, to apologize to the family of Sankara and the people of Burkina Faso? What does the verdict teach us about the tenacity of a people in the pursuit of justice?

Who was Thomas Sankara?

Popularly known as ‘Africa’s Che Guevara’ and considered as the founding father of Burkina Faso, Sankara was a military officer, pan-Africanist, and Marxist-Leninist revolutionary. In 1983, he was appointed as prime minister following a coup d’état by President Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo.

Sankara was a vivacious left-wing thinker whose outspokenness, intellectual prowess, political insight, and charisma won him sweeping support across the country. It also made him several enemies within conservative circles. He was arrested numerous times and finally forced out of office in May 1983.

On August 4, 1983, with the support of his childhood friend and military comrade, Blaise Compaoré, Sankara became Burkina Faso’s president following a military coup, which toppled the Ouédraogo administration. Sankara and Compaoré formed the National Council of the Revolution which sought to democratize, modernize, and economically liberate Burkina Faso.

Merely four years later, though, his tenure was cut short after he was assassinated in another coup, which was largely deemed to have been encouraged by certain external forces for the benefit of his friend Blaise Compaoré, who took over as president shortly after and ruled for 27 years.

The Sankara Years: A Man Ahead of His Time

A vocal anti-imperialist and champion of liberation for oppressed peoples globally, he was inspired by and worked closely with leaders of the Non-Aligned Movement, particularly Jerry Rawlings of Ghana, Fidel Castro of Cuba, Che Guevara of Chile, and Samora Machel of Mozambique. He coined the term “neocolonialism”, encapsulating, among other things, the grip he felt organizations such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund maintained on African economies.

On assuming office, Sankara embarked on a “democratic and popular revolution” based on a complete re-building of the entrenched systems that he felt stagnated the country’s progress and potential. He changed the name of the country from Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, loosely translating to “Land of the Upright” to highlight his vision for his people. An advocate of integrity and decency in the conduct of government affairs, Sankara reduced the salary of government officials and public servants, including his own, to a reasonable level. He stopped the use of government chauffeurs and first-class airline tickets, replaced luxury cars with bikes, and even had air conditioners removed from certain briefing rooms, including his office. In his eyes, it was abominable for a select crop of the population to enjoy unmerited privileges while its majority languished in destitution.

To foster health and children’s development, he established a nationwide child inoculation program. In the first few weeks of his presidency, approximately 2.5 million children were vaccinated against meningitis, yellow fever, and measles. By the end of his tenure, over 80% of Burkinabé children had been vaccinated against at least one infectious disease. Sankara also increased school attendance and literacy rates for all Burkinabés from a dismal 13% in 1983 to 73% in 1987.

A gender equality champion, Sankara believed that “women hold up the other half of the sky”. He always said that he “heard the roar of [their] silence” in Burkina Faso. Through his parliamentary Women’s Union of Burkina, he mandated equal access to education, outlawed forced and child marriage, criminalized female genital mutilation (FGM), recruited women into the military, guaranteed paid maternity leave, introduced inheritance for widows and orphans, and repeatedly pressed the need for men and women to equally participate in household and secular work. He also increased the number of women holding senior government positions, making it constitutionally obligatory for presidents to have at least five women cabinet ministers throughout their tenure.

To ensure the country’s self-sufficiency, Sankara rejected Western aid and imported goods, boldly reiterating his view that African countries were shackled by their dependence on foreign powers for their sustenance.

A visionary who saw the coming disaster of climate change, Sankara promoted reforestation. He oversaw the planting of over 10 million trees in a year. Meanwhile, he redistributed land from local chiefs and foreign companies to poor farmers, spurring mass nationwide production of crops like cotton, cocoa, and wheat.

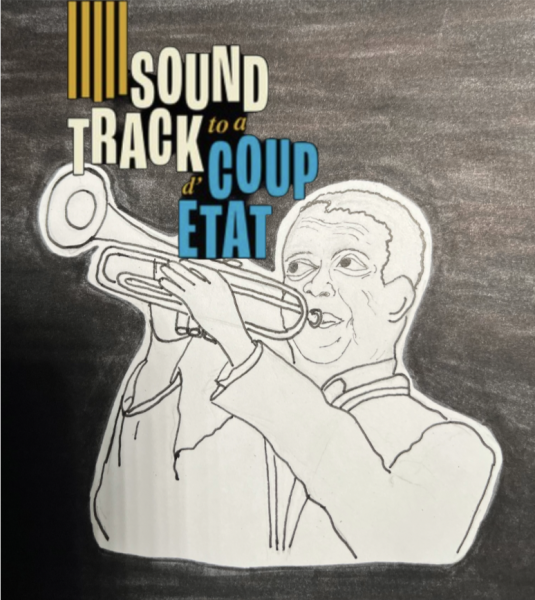

As a talented guitarist, Sankara played in a jazz band and could be seen, even as president, jamming with his comrades. He composed the country’s new national anthem. He was also a very good friend of Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, the late Nigerian Afrobeats superstar and political activist.

Too Good to Last

While Sankara had the support of many Burkinabés, he had internal and external critics as well as enemies who translated his actions as overzealous, irreverent, and outrightly detrimental to their personal and national interests. He was always conscious of the risks he was taking to liberate his people. In a speech in 1986, he said, “…I have accepted the fact that I could end it all in a violent death because we have a lot of enemies. Once that has been accepted, it is a matter of time. It could be today or tomorrow.” He concluded his eerie prophecy by adding that in the future, people will not say “that’s the former president of Burkina Faso” but “that’s the tomb of the former president of Burkina Faso”.

On October 15, 1987, Thomas Sankara was killed in a military coup, widely believed to have been executed for the benefit of his best friend, Blaise Compaoré. There have been speculations that external actors instigated Compaoré to eliminate Sankara. Compaoré assumed power and led an authoritarian regime that would see the nation spiral into socioeconomic decline and instability. Although he became a civilian president, organizing several elections, his power was still deeply tied to the military establishment. Compaoré’s tenure was marked by rampant abuse of power, which led to his ousting, after 27 years, and exile in neighboring Cote d’Ivoire in 2014.

Who killed Sankara?

For the 27 years of Compaoré’s regime, every attempt to find Sankara’s murderers was thwarted. It took a change of government for the April 6 verdict to be pronounced after a year-long trial of the 14 accused, who were all sentenced to life imprisonment. Compaoré—who had fled to Cote d’Ivoire and acquired the country’s nationality through marriage, thus avoiding extradition—and his former chief of security, believed to be hiding in a neighboring country, were tried and sentenced in absentia.

Justice Delayed is Not Always Denied

After 35 years, the verdict on the assassination of Sankara has shown that despite all the efforts made by the previous authorities to suppress justice, including claiming that Sankara died of natural causes, it has, finally, been served. For prosecutors, legal experts, and all lovers of truth and justice in Burkina Faso and beyond, the outcome of the trials is a victory for the rule of law and the pursuit of justice. Sankara’s family, including his widow and sons, as well as the families of other victims of the coup, can begin to have some closure.

Hopefully, this verdict will send a clear warning to all leaders—military, political or civilian—committing or abating human rights atrocities that, not only is the arm of the law far-reaching, but it also bends towards justice.

Sankara Always

Over three decades after his death, it is interesting to see how Sankara is still adulated in Burkina Faso and beyond. The assassination of a man, whom many Burkinabés and Africans saw, and continue to see, as a shining example of authentic and service-oriented leadership sparked a light that can never be extinguished.

Warned by his security details a few days before his death, Sankara, prophetically replied, “…while revolutionaries as individuals can be murdered, you cannot kill their ideas.” According to witnesses, moments before his death, Sankara ordered his counselors to “….stay; it’s me they want.”

Even after justice has been served and the tendering of apologies by a person considered to be one of the major instigators and beneficiaries of his assassination, Sankara has refused to die. Rather than trouble the homestead, it is hoped that only his ideas will continue to burn in the hearts of those who love and respect him.

Click here for a complete list of sources.

Hello, everyone! My name is Temisola and I am in my senior year at UNIS. I like to write articles about current events. I also enjoy writing opinion pieces...