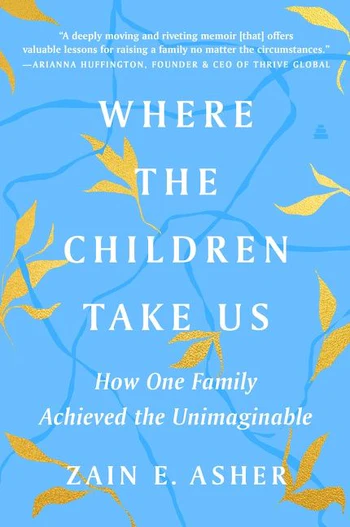

Book Review: Where the Children Take Us

Raising a Future Oxford- and Columbia-Trained CNN Anchor, Oscar-Nominated Actor, Medical Doctor, and Entrepreneur through Tragedy)

You may have seen her on TV reporting on the biggest international business and economic issues of the day. You may have read or watched her ground-breaking reports on the Chibok schoolgirls kidnapping in 2014, which, by the way, won her that year’s Peabody Award. You may have seen her anchor “MarketPlace Africa” or “One World with Zain Asher” on Cable News Network (CNN) where she is known for her poised demeanor and in-depth analysis. Watching her on the television, who would have ever imagined that she went through such incredible life challenges, which could have derailed her life trajectory and deprived her worldwide audiences of such talent? In her captivating memoir, ‘’Where the Children Take Us: How One Family Achieved the Unimaginable”, Zain Ejiofor Asher recounts her phenomenal story.

A tragic beginning

“Where The Children Take Us” begins on a Sunday in Zain’s childhood home in south London. That day was full of anguished anticipation as her family awaited the news of her father and brother, who had been involved in a car accident while traveling in Nigeria. While her eleven-year-old elder brother, Chiwetel, survived the accident, her 39-year-old father, Arinze Ejiofor, did not make it.

Having survived a brutal civil war, the death of her younger brother, and a two-year famine, Zain’s mother, Obiajulu, had fallen in love with Arinze, “the first boy she ever danced with” and moved from their village, Oyofo-Oghe, in eastern Nigeria, to London, to study and build a better life. They studied and worked hard, building their pharmacy business with the aim of travelling the world, and returning to Oyofo-Oghe to give back to their community.

Not only did Obiajulu’s dreams evaporate with Arinze’s death, but she was also now saddled with a five-month pregnancy, two teenage boys, and five-year-old Zain. To say that Obiajulu was lost would be an understatement.

Zain gave a vivid account of her mother’s struggle with life after her father’s death. Feeling dejected about a future without Arinze, and distraught that her second son, Chiwetel, was lying in a hospital bed in Nigeria, Obiajulu would spend hours locked in her room, barely ensuring Zain and her eldest brother, Obinze, had something to eat. She hardly spoke to her children, who, it later turned out, were processing their traumas in different ways, particularly Obinze, who struggled to readjust to life at school. At home, he couldn’t share his emotions with Obiajulu who was depressed and didn’t want to talk to anybody. Gradually, Obinze began to skip classes and get into fights. He would shout at his teachers. They had sent letters home to Obiajulu, who never responded. Finally, Obinze, the brilliant boy, on his way to a prestigious school, was expelled from. He drifted into some rough areas of south London, spending nights away from home.

Zain recounted her emotional struggles as she entered school for the first time in the fall after her father’s death. Her grandmother, Mama Nnukwu, who had come from Nigeria to take care of them, though loving in her own ways, “lacked the gentle emotions” Arinze embraced. He had spent the month before his death to prepare Zain for school. He read books to her, practiced tying her shoelaces and hanging her coat. He explained the school routine, how to make friends, and listen to teachers. However, when Mama Nnukwu took Zain to school, there were no hugs and kisses other children received from their parents, grandparents, or guardians. Mama Nnukwu would lead her “by the hand toward a teacher, thanked them, waved goodbye, and left”. Over time, Zain became resentful of other children who played together happily on the climbing frames and merry-go-rounds. She struggled to understand why other children were happier and why her father didn’t keep his promise of dropping her off at school.

Even when Chiwetel came back to London, he was still nursing the physical (deep scar on his forehead) and psychological trauma of the accident. He was the last person to see Arinze alive, the last person to hold his hand, the last person to hear his voice. For the family, he was “a bridge to Dad’s spirit and a breathing reminder of his tragic death. …He would carry that weight of crushing guilt for the rest of his life”.

During the early days and weeks of Arinze’s death, Obiajulu missed several doctor’s appointments for her pregnancy, potentially endangering the life of her unborn baby as well as hers. She also neglected the pharmacy business she had built from scratch with Arinze almost to the point of bankruptcy. Things were falling apart in the Ejiofor’s household.

Turning things around

Zain affirms that a call from Obinze’s school administrator informing Obiajulu of her son’s expulsion jolted her out of her depressive state, opening her eyes to the downward spiral her family was getting into. “Is this really what’s become of my family?” she exclaimed and stormed into her room after the school administrator refused her explanation and demanded an understanding of her predicament.

When Obiajulu woke up the next morning, she called her children for a family meeting and promised that things would be different henceforth. “She fell to her knees and touched us for the first time in weeks….We melted into her embrace…She would make life good again. My mother, like countless Nigerian mothers before her, would not let us down.”

Mama Nnukwu equally played an important role in the revival of the Ejiofor’s household. A tough, strict, and diligent woman who had suffered some of life’s greatest hardships, she had to grow up quickly, fending for herself at 13 and losing a son who died of starvation during the Nigerian-Biafran war. Against all odds, she raised nine well-disciplined children. Where she came from, “people took action” when disaster struck. And this is exactly what Mama Nnukwu did. She watched over Zain and her siblings. She tended to Chiwetel’s wounds and watched Obinze closely as Obiajulu tried to keep him occupied while searching a new school for him. She meted out the “Nigerian mother’s treatment” to her grandchildren, commandeering them to carry out house chores, without any room for explanations or refusals.

Overtime, Obiajulu started to apply Mama Nnukwu’s “method”. One Sunday morning, as Zain and her brothers watched the television, which according to her, felt like their “only refuge that morning”, Obiajulu barged into the room, snatching the remote control, and switching off the television. She marched them to the dining table, which had three books on it. Handing one to each child, she laid out her new plan: it was time for change. There was going to be structure and discipline, including “strict curfews for the boys, a long list of chores, weekly reading lists, regular family time to discuss academics.”

With television now prohibited, Zain and her siblings were tasked to read one book each week and present a summary at dinner time. Over time, books became a centerpiece of the Ejiofor household and literary debates occupied their down times at home. Though the boys were not early converts to Obiajulu’s ‘reading club’, quizzes from books read sparked positive sibling rivalries, leading to more book reading to outwit one another. Trips to libraries and museums became commonplace. All the while Obiajulu asked questions, sought more resources, and developed new incentives to engage Zain and her siblings.

She did everything possible to get Obinze back to school, nurtured Chiwetel back to good health and honed his gifts in the performing arts, while encouraging her children by exposing them to stories of black people who had excelled in their fields. She would share newspaper clippings of successful people of African origin.

The march to academic success and international renown

It did not take too long for Obiajulu’s strategy to start bearing fruits. Within a short time, Zain had become “a walking encyclopedia” of Black resilience and empowerment. She had started believing in her mother’s affirmation, right from when she turned 13, that she would be attending Oxford, “a place of kings”, which she did. She later attended Columbia University for her postgraduate degree in journalism.

One day as Zain and Obiajulu were watching the news, Femi Oke, a British-Nigerian presenter on the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) came on air. Zain was so inspired to see a Nigerian woman like herself in such a distinguished role that this remained with her through high school and college. Oke, who later joined CNN, mentored Zain as she prepared to join the Network too.

In the meantime, Zain’s siblings were steadily climbing the ladder of success, with Obinze becoming a successful entrepreneur, Chiwetel, an Oscar-nominated actor, and Kandi, the baby of the family, a medical doctor.

The importance of family cohesion and resilience

This book clearly depicts the importance of family cohesion. We see the extended family of the Ejiofors rallying around them immediately after Arinze’s death. Obiajulu, and her children, at different stages, also showed resilience and the desire to succeed against all odds. Zain rightly presents her family situation by affirming that “There is a tragedy in my story, but my story is not a tragedy”.

Where our children can take us

In many ways, this candid, gripping and heartfelt book reads like Amy Chua’s The Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, excluding the tragedy of the Ejiofors. It does, however, feature similarities in Chua’s controversial techniques of raising successful children. These include the unwavering dedication to excellence, the extra hours spent diligently reading for school and the often unorthodox forms of instilling discipline. Like Chua, Obiajulu (and Mama Nnukwu) applied tough love, which laid the foundation for Zain and her siblings’ outstanding success.

I do feel it would only be right for the book to have been co-authored by Obiajulu. However, to be fair to Zain, she acknowledged in the preface that “it is my mother’s story more than mine”. Notwithstanding, from the tragedy of Arinze’s death, Obinze, Chiwetel, Zain, and Kandi have taken Obiajulu (and the Ejiofor name) to places she only could have dreamt of.

Hello, everyone! My name is Temisola and I am in my senior year at UNIS. I like to write articles about current events. I also enjoy writing opinion pieces...