The Significance and Evolution of Women’s History Month

Photo by Katie Crampton (WMUK)

This month we celebrate Women’s History Month. Although women throughout the last 150 years have worked tirelessly to obtain not just better rights but a better place in the world, the event is rather new on the wider timeline of history as it was only very recently when limits on women’s rights were widely reduced and the topic became significantly more understood and welcomed in discussion. Even in the 21st century, the economic, political and social achievements of women that we celebrate each March should be at the forefront of our minds, as they are continuously overlooked by society. Therefore, the question that arises this month is: “how did Women’s History Month develop, and why is it important to celebrate?”

Stories of women standing up against the status quo and the injustice imposed on them by patriarchal societies are persistent throughout history; however, women’s rights did not significantly change, at least legally, until the mid-19th century. Feminists consider there to be four waves of feminism that have occurred over the years. For historical purposes, this article will focus on the ‘first wave’ of feminism, whose exact beginning and end is up for interpretation but is widely believed to have occurred from 1848 to 1920. This ‘first wave’ refers to the West’s first sustained political movement for political equality run by the ‘suffragettes’ of the 19th and 20th centuries, whose main target was the enfranchisement of women.

The first attempt to organize a reform movement for women’s rights occurred in 1848, Seneca Falls, New York, when a group of over 300 women gathered to outline the direction for the developing women’s rights movement. This meeting was headed by renowned suffrage activists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, who called for American women to be granted “all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of the United States.” Stanton, as well as other women reformers of this era such as Susan B. Anthony, continued suffragist efforts to bring about social change following the Civil War in 1865. Leading up to the Seneca Falls Convention, the growing female involvement in the abolitionist movement spurred female political participation in America, as ideas on the provision of equal rights were held not only through a feminist mindset but a racial one as well, putting the intersecting identities of American women into the spotlight.

However, the suffrage movement at this time was widely a ‘white’ movement, because racist rhetoric present at the time formed a separation between the efforts of white and African American women. Stanton and Anthony were mainly invested in the implementation of voting rights for white women, but shared sympathy for the Black women whose rights were also under question; thus when the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 promised citizenship rights and equal protection under the law to “persons born or naturalized in the United States”, they wondered whether this law would similarly apply to women, both black and white. Ultimately, the Fourteenth Amendment defined voting rights as only applicable to “male citizens”, much to the dismay of activists who would fight for the rest of the century to obtain equal rights. However, the 14th Amendment was highly hypocritical in the sense that while all men could vote on paper, Black men were systematically disenfranchised, and like their female counterparts, would face many more decades of struggle continuing on to the present day.

The struggle continued despite multiple refusals by the US Congress to pass resolutions enshrining women’s suffrage in the Constitution throughout the late 1860s. The movement faced heavy debate after Stanton publicly denounced the extension of voting rights to Black American men, losing the movement support from African American women. Despite these setbacks, the emerging suffrage movement focused its goals on obtaining equal voting rights, starting two distinct organizations in 1869: the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Neither organization achieved much broad public support, and they eventually merged in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) following an onslaught of volunteerism by middle-class women in women’s clubs, societies, and organizations to aid the suffrage movement in obtaining widespread publicity. The audience of the new joint group was quite narrow, as the suffrage movement consisted mainly of middle to upper-class women who were often working-class. The socialist and leftist women who joined the suffrage movement were a minority, as most women of these ideologies did not see suffrage as a means to an end. Rather, they pushed for wider social change and a long-term revolution of women’s rights. Despite some minor successes for all women to maintain voting rights, voting rights are arguably still being fought for today in America as recent elections have been fraught with new state laws making voting more difficult for marginalized groups.

From this point onwards, the movement struggled due to the onset of post-Civil War racism and segregation known as the Jim Crow era; however, it also reignited support from Black suffrage activists such as Mary Church Terrell who decried the disappearance of civil and political rights for African Americans. Another prominent voice of the era was well-known African American abolitionist and women’s rights activist, Sojourner Truth. Truth was an outspoken defender of women’s rights, performing her “Ain’t I A Woman” speech in 1851 in which she argued that Black women were not afforded the rights white women were fighting for. Intersectionality added to the suffrage movement, as it expanded the voices being heard by Congress and called for revisions to voting rights and the involvement of both women and African Americans in the political process. The complex efforts of the NAWSA eventually prevailed in the late 19th century, with women in Wyoming gaining full voting rights in 1869, and subsequently, Colorado (1893), Utah (1896), and Idaho (1896). These successes continued into the 1910s with Washington, California, Arizona, Kansas, and Oregon gaining voting rights between 1910 and 1914.

Following these events, activists called for an acceleration in social change. Thus, in 1913, suffrage activist Alice Paul formed the Congressional Party, later named the National Women’s Party. Through this movement, the suffrage movement was able to obtain many of its long-term goals through a system of civil disobedience which included picketing, mass rallies, and marches; techniques that Paul had borrowed from the British suffragettes with which she worked during the 1910s. The movement attracted newfound attention, drawing in hundreds of women and eventually leading to key victories in 1917 in Arkansas and New York. Equal voting rights in New York significantly altered the playing field, as they convinced President Woodrow Wilson of the predominance of the suffrage movement. The equal rights amendment originally proposed by Stanton and Anthony in the 1870s was reintroduced; it was passed by the House of Representatives on May 21, 1919, by Congress on June 4, 1919, and ratified on August 18, 1920. Equal voting rights were finally secured for American women, but there would still be decades of struggle to include African Americans and other minority women in this promise.

This would lead to what feminists consider the second wave of feminism, occurring from around 1963 to the 1980s. The era was characterized by renowned authors such as Simone de Beauvoir’s Second Sex and Betty Friedan’s Femme Mystique, both of which contributed to highlighting the system of oppression imposed by patriarchal American society. Their novels caused an uptake in protests and demonstrations arguing for increased equality between American men and women as they revealed that the struggle for feminists’ unifying goal of social inequality could be waged by anyone and through any means. The third and fourth waves of feminism started in the 1990s and continue to the present day, with the third wave focused on counterculture and the sexual revolution, while the fourth and current wave focuses on the representation of women in media and intersectionality. The feminist ideals that emerged from the suffrage movement have grown to protect so much more than equitable voting rights, having evolved into a safe space for the progression of women’s rights and identities.

As feminism progressed and evolved throughout the century, so too did the global perception of the contributions of women to socioeconomic, political, and technological growth, spurring the celebrations that would form our modern concept of Women’s History Month each March. National Woman’s Day was held officially for the first time on February 28, 1909, in New York City and was organized by the Socialist Party of America. The concept of “woman’s day” spread to Europe where the first International Woman’s Day occurred in Paris on March 19, 1911, with one million people participating in rallies worldwide. In the Soviet Union, Vladimir Lenin declared Woman’s Day an official holiday in 1922, spurring other states such as China and Spain to officially adopt the holiday as well. It occurred unofficially on a global scale until the United Nations started sponsoring the day in 1975, adopting a resolution to observe International Women’s Day and citing their aim as “To recognize the fact that securing peace and social progress and the full enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms require the active participation, equality and development of women; and to acknowledge the contribution of women to the strengthening of international peace and security.”

The annual month-long celebration each March grew out of the original week-long Women’s History Week celebration organized by students in the school district of Pomona, California in 1978 with the aim of “writing women back into history”. Over the years, it caught on, leading to President Jimmy Carter declaring the first presidential proclamation of Women’s History Week on the week of March 8 in 1980. It wasn’t until 1987 after a group of women— Molly Murphy MacGregor, Mary Ruthsdotter, Maria Cuevas, Paula Hammett, and Bette Morgan— formed the National Women’s History Alliance in 1980 and issued numerous petitions to Congress to expand the week-long celebration to the entirety of March, that Women’s History Month as we now know it was created.

Today, Women’s History Month focuses less on the struggle American women endured to achieve equal rights and encompasses a celebration of the achievements and contributions of women to society socially, politically, and economically. The celebration is exclusively an American concept, and it is only International Women’s Day that is celebrated internationally. This year, the 2022 Women’s History Month theme is “Providing Healing, Promoting Hope”— a tribute to the American caregivers and frontline workers who have worked tirelessly to provide healing and hope throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. Following the trauma brought by the pandemic, it is important to appreciate and honor the ways women have contributed to bringing about hope and healing as doctors, teachers, emergency response workers, and in many other ways.

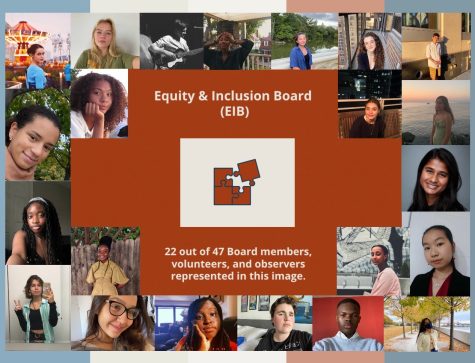

At UNIS, our community has been celebrating Women’s History Month through last week’s 2022 Equity and Inclusion Board Conference, which focused on the “overarching topics of gender roles and Feminism and its intersectional effects on marginalized groups.” The conference celebrated how Feminist theory and gender norms are manifested in multiple facets of life, and honored contributions made by feminists to furthering social change. The conference reflected the importance of learning about and discussing feminism and gender roles in an academic atmosphere.

Beyond UNIS, students and staff can celebrate Women’s History Month by attending webinars and virtual events such as those held by the Smithsonian Institute and the Library of Congress, which focus on women’s contributions to American politics. The National Women’s History Museum also features numerous online events this month on a range of topics, including conversations with female authors and politicians. More generally, this month you can take the time to support women’s contributions by watching movies directed by women, supporting women-run small businesses, and reading books and articles on women’s history, feminist theory, and global issues affecting women. Some recommendations from UNISVerse include the Combahee River Collective Statement, This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color edited by Gloria Anzaldua, A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf and Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde.

I am in the class of 2023 and I write about many different topics. I enjoy baking and reading in my free time and my favorite classes are Global Politics...