The Never-Ending Story: UNIS’s Waste Management Saga

On April 22nd, Earth Day, UNIS announced plans to hire a paid Sustainability Director for each division of the school to begin tackling the issue of sustainability in a dedicated and “schoolwide approach,” as Dr. Jennier Amos of the administration stated. Specifically, these coordinators—who have been hired as of this wriring— will address “research about sustainability, connections in the curriculum with the SDGs to increase knowledge and awareness, and coordinating activities around this topic, among other things,” with one crucial issue being waste management, as outlined in the Sustainable Development Article 12– Responsible Consumption and Production— an important and often unheeded goal. This is a major step in institutionalizing the care for the environment that is so embedded in UNIS’s values, especially after what has been a year of halted progress and setbacks.

Sustainable waste management at school is not, in theory, a very demanding or complex endeavour. We have the bins: recycling, compost and normal trash, to put in classrooms and the cafeteria where students can dispose of their waste correctly. At the end of the day, maintenance staff empty their contents into communal bins for their respective categories, after which we send off the bins to their corresponding plants (recyclable waste goes to the recycling plant, organic waste to the composting plant, etc.). However, as put by an anonymous teacher, when it comes to fully committing to the UN values in relation to this issue, the answer has long been “it’s too complicated,” and even with the administration’s engagement, many challenges remain. Though this is a marked example of progress, it is important to understand how UNIS got to this point and what our problems have been, to know that the process of galvanizing our waste management does not end here.

Prior to 2019, UNIS’s waste management infrastructure largely existed in a state of box-checking ineffectiveness. We had the recycling, compost, and trash bins (though not everywhere) and the Department of Sanitation-issued signs which told students where to throw their waste products. However, the items on the signs did not always align with the items the cafeteria sold, and bins were often contaminated by unknowing or perhaps even careless students. While the varied selection of foods and drinks in the cafeteria is something most students enjoy, this luxury often makes it harder to correctly sort trash. The sushi that the cafeteria sells, to give one telling example, involves food waste which goes in the brown bin with the wooden chopsticks and any napkins, a plastic container that goes in the blue bin, and fake grass and soy sauce packets which, though made out of plastic, must go in the trash. That’s how the waste management process works for just one item, and with an ever-increasing menu, students’ knowledge about what goes where has not kept pace. Compounding this, harmful misconceptions and misinformation abounded, such as the idea that once recycling waste was sent to the recycling plant it would be sorted and recycled (it’s not), or the lack of awareness that a recycling/composting bin only needs to be 30% contaminated to be diverted into a landfill.

These culminated for many into a collective it’s-only-one-bottle mentality, with the meniality and seeming futility of this task prompting a lack of concern for the issue recycling represents. This is not to say that individual students were already not taking the necessary steps and taking care of their waste appropriately, but because this largely relied on the individual initiative it only took a minority to invalidate the efforts of others. Among some students, there circulated the rumour that even the non-contaminated recycling and compost ended up in the dumpster-bound pile at the end of the day. Whether it was true or not, this surely added to the careless attitude, by emphasizing the futility of any efforts. The result was that while, due to misinformation, disinterest, or complacency, the issue of waste management remained untrumpeted, UNIS was pitifully underachieving.

Ms. Martinelli Torres, a UNIS parent, was at a community service parent meeting in 2019 when the idea of a parent sustainability group was floated, and she jumped at the opportunity. She had begun paying attention to this issue after seeing that “obviously, this was not something that was being addressed.” Around the same time, some students, such as Natalie Meola, T2, showed a similar perspective, saying, “It seemed like an overlooked issue that not many people cared about or valued, which was very upsetting to me.” The group was created, with other concerned parents jumping on board, and after meetings with Dr. Dan Brenner and the administration where this growing concern was discussed, the feeling was that they really “got it.” With pressure from both parents and students, recycling and compost bins were installed throughout the school, and programs like the “Green Guides”—MS students who would help remind and direct the other students to throw everything away in the right place— were created.

The next step, according to Ms. Torres, was an audit, carried out by Common Ground Compost in October of 2019. The findings shed light on UNIS’s situation: 87% of the waste coming from the kitchen was in the wrong bin, only 40% of what was in the cafeteria recycling bin was recyclable, and 89% of what was thrown in the trash should have gone elsewhere. Despite the considerable work put in, UNIS still had a lot of ground to cover. However, the audit gave several recommendations on how to proceed, and with tangible data from which to base the next steps, as well as increased support from the administration, UNIS’s sustainability movement continued its renaissance. Students and teachers were able to push for the addition of two water fountains to decrease the use of disposable bottles, the switch to aluminum bottles, and the switch to reusable dishes and cutlery. Also, with sustainable initiatives in the JS such as the Composting Club, led by science teacher Ms. Vanessa Go, as well as the opportunity for UNIS to compost for free, unlike other private schools, with the Department of Sanitation (an opportunity also spearheaded by Ms. Go), it seemed that UNIS was on the way to becoming a more sustainable school. However, as Ms. Torres said, “things sometimes get sidetracked. When COVID came, things just halted.”

COVID rendered many of the initiatives that were beginning to bridge the gap between UNIS’s duty and reality impossible. The initiatives students and parents were working on were usually not meant to be long-term, but instead aimed at building a foundation upon which, eventually, responsible waste management would be undertaken—for lack of a better word— organically. This aim entailed initiatives directed at improving waste management immediately, involving the administration more closely to ultimately make this a matter that it would take care of like any other. However, talks about long-term administration involvement has stalled. Most initiatives had been the product of dedicated voluntary work from parents, teachers, and students, often middle school students, who made suggestions, brought in outside support, and pressured the administration to mobilize the school’s resources. As Ms. Torres said, engaged parents were there “day in and day out, pounding our ideas through.” However, without parents’ support or some sort of administration infrastructure to deal with this topic, the burden lay on students and a few teachers, yet, avenues for them to engage in this issue were limited. For example, while students still clearly had access to the cafeteria, COVID made it difficult to engage in any on-site activism, and their scrutiny of its affairs—managed separately from UNIS by Flik dining services— was frowned upon, with students not being allowed to take pictures of the bins to document the level of contamination. Consequently, information on the waste-management situation was—and still is— hard to come by for engaged parents, as have been opportunities for students to change their classmates’ habits. Furthermore, with COVID-related issues clearly becoming the priority, there wasn’t much of an open door for students to continue to campaign with the administration.

Due to COVID, the Green Guide program was no longer feasible and the City of New York cut funding for the Department of Sanitation, leading to the end of the free composting service UNIS relied on. The kitchen stopped using reusable dishware and silverware for sanitary reasons, and though the administration did make a considerable effort to use sustainable supplies, they weren’t completely able to adapt new supplies to the situation. For example, UNIS invested in compostable containers, though there was nowhere to compost them anymore, and even in the increasingly rare instances of composting pickup, many of these materials got diverted. The lost momentum has also been significant. Much of the education or habit-building that was in motion before the pandemic, stimulating constant reflection on the issue of waste management, has not only been stalled but most progress has been washed away. This has been especially acute in the Junior School, where the chance to instill this sensibility in many students who are at an impressionable age has been severely impaired. Without students or parents being able to champion the cause, and with no administrative infrastructure to carry on these initiatives, sustainability had been all but forgotten. As a glance into the homogeneously contaminated waste in different bins might have shown it seemed like most progress in the actual disposal of waste has also been erased. Overall, “we’re back where we started,” judged Ms. Torres in April.

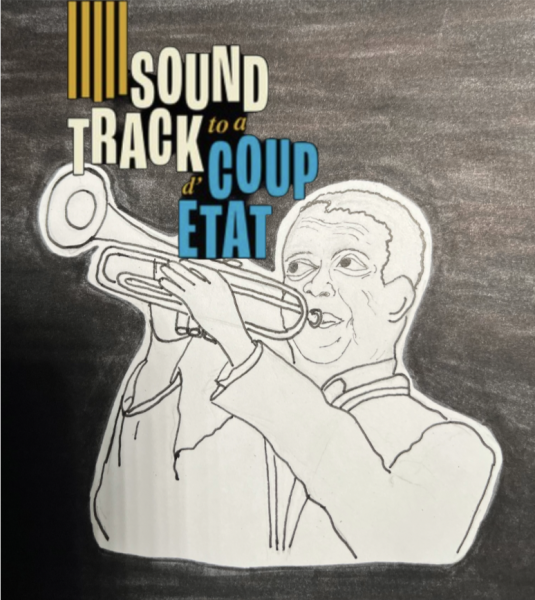

Of course, it is impossible to deny that COVID was the most pressing and demanding issue that our school was facing, and still is, taking up the administration’s attention due to innumerous logistical and health-related issues. Moreover, UNIS faces other problems, not least the work on diversity and equity, which has rightly become an increasingly central part of its work. Evidently, the school has a lot on its plate, and their lack of attention to waste management is understandable to a certain extent—every IB student, pounced upon by obligations from all angles, should sympathize. However, this reflects a dangerous attitude that has been taken with sustainability far past the confines of UNIS, and far before the pandemic started. With only 18% of waste from homes and 25% from firms being recycled in NYC before the pandemic, countries around the world flouting their Paris Agreement obligations, and temperatures rising across the globe due to their lack of engagement, countries and institutions never seem to heed the problem of sustainable waste management. Despite there being some efforts from the administration, sustainability simply hadn’t seemed to be a priority, with inconsistencies that jeopardized any incremental improvements going unaddressed. Compared to the attention shown to this issue on the walls of our school and on the website, where the slogans “Greening the Blue” and “A Better World,” are inextricably linked with sustainability even if it doesn’t pertain only to it, genuine attention to tackling the issue had been underwhelming.

Furthermore, this is not the type of issue that can be addressed only with concentrated, erratic bursts of effort that have characterized previous attempts to do so. Sustainable waste management involves gradual habit-building and education, so that students and teachers are aware of the issue’s importance, know how to act accordingly, and have the infrastructure to do so. All of this is impossible under the stop-start process that erases all our progress when something more urgent comes up. This furthers the argument for a section of the administration to be dedicated to this issue, so that this problem, which needs perpetual attention, doesn’t rely on the attention of officials who have much else to deal with. It is these challenges which make the announcement of the new Sustainability Coordinator positions all the more exciting, as it is precisely to this problem of inconsistent attention that it is geared. With a constant effort devoted to this issue, there is an opportunity to act effectively.

UNIS must commit to educating students on this matter. Still today, many students cling onto the misconceptions and lack of appreciation for the complexities of waste management, meaning any initiative swims against the current. Students I have spoken to often show a lack of knowledge about what happens to their waste—for example, few know that organic scraps like banana peels thrown in the trash rather than in the compost bin will not decompose due to the lack of oxygen in the landfill they will most likely be dumped into.Before writing this article, I didn’t know that either. With this kind of a lack of knowledge, the problems with sorting a variety of materials persist, as do accountability-reducing misconceptions like that the maintenance or recycling/composting plants sort our trash, which could be solved with simple commitments from the school.

This announcement does represent a potential step forward, but it should not be an excuse for passiveness, even when it comes to involvement of the administration . Though this is the most tangible action that the school has taken in some time, UNIS’s rocky history should make any optimism a cautious one. It remains to be seen how much sway over school decisions, which encompass more than sustainability, and how much access to the school’s resources the new sustainability coordinator will have. Also, though this represents progress, a single person per division is likely to have the immediate game-changing impact desired, and for an issue as important as this, gradual, plodding advancements are not enough.

Of course, it is easy to harp on the administration’s record on this issue and think that the ultimate fate of this issue relies on their commitment without turning our eyes to the other obvious player in this issue: the student body. After all, it is our trash in discussion, and we are the ones who contaminate it and have the ability to stop. As mentioned above, the lack of sustainability education received by most UNIS students can contribute to the unconcerned attitude towards the issue, but at a certain point, we have to take responsibility ourselves. Though a nuanced knowledge of what happens to our trash can help turn our attention to waste management, it shouldn’t take much to know that sustainable waste management is important—in this day and age, there’s really no explanation for being ignorant about this. With this basic knowledge should come a basic sense of ownership about the way you dispose of your waste. As discussed, with so many different materials going into the diverse options offered by the cafeteria, it is difficult to keep track of what goes where, especially when there hasn’t been a true effort to explain this. However, a basic effort, one which is often lacking, is still possible, and can be consequential if undertaken by most. As Ms. Torres noted, “everyone can and everyone counts.”

Also, as many of the challenges UNIS has faced during COVID are overcome as the country continues to be vaccinated, it is important to have faith in our administration, especially given this major step forward. However, students should continue to hold the administration accountable and push for changes through the vehicles they do have, like Student Council or sustainability-involved organizations— if anything, this is the time to stamp down on the gas pedal.

There are students who have previously been involved in this issue, and who have been crucial to any progress UNIS has made, but not as many as one would hope. From the pro-sustainability Instagram stories ranging back to the Amazon fires, to the adamant strides for racial equity, UNIS students often display the values of the SDGs, and the willingness to act on them. If students understand the complexities and outsized impact of waste management in our immediate vicinity, one that goes beyond sustainability into areas like racial equity, the impetus for students to get involved should be even more forthcoming. For years now, predominantly black neighbourhoods like the South Bronx and Southeast Queens have borne the brunt of NYC’s trash disposal and the negative effects that come with it, an example of “environmental racism” which has only begun to be alleviated since Mayor De Blasio signed a 2018 bill to begin to relieve these neighbourhoods. When we dispose of our waste inadequately, it is these communities which feel the effects. UNIS and its students’ commitment to doing more for people of color should not limit itself to the confines of our school community, and we must ensure that our actions should be coherent with our values in all their side effects and implications. Taking responsibility for your waste is a logical extension of and natural way to stand by the values you hold in high regard.

We are not easily impressionable JS students, and in the lack of attention given to sustainability through the years, many of us have built lazy habits which can cause some inertia when it comes to assuming responsibility. I can say that I’m probably guilty of this. But we’re still in high school, far from mature and done growing, and this is a painless, undemanding, and accessible chance to shape your habits and those of others, both now and in the future.

Even if the school has made steps forward, this issue still largely depends on us. Individually, students may feel like they do enough, but outwardly, we’ve been apathetic about it. So just give it a little more attention. You don’t have to be an activist, but just think for a moment longer about where you throw your food, educate others who you think may not grasp the importance of the issue at hand, and if you want to get engaged, be demanding of your administration. This is not just a UNIS problem but a global one, and while we can’t fix it for everyone, the solutions to our immediate issues are feasible and within reach.

Every IB student understands the difficulty of having to deal with multiple obligations at once, but we should all realize that we still have to fulfill them. UNIS seems to be going in the right direction, but as the sustainability coordinators begin to engage in the school’s issues, UNIS’s progress will be something to watch and not forget about in ignorant satisfaction. This issue is far from over.