A Pessimist’s View on IB and Exams

A Brief Note to the Administration, Counselors, Teachers, Parents …

This article is based on conversations and interactions I have had with fellow IB students. It would be wrong to say that certain people do not feel this way. However, the article above is not to be taken completely literally. As the title suggests, it reflects a pessimist (perhaps even nihilist) view towards exams, the IB, and indirectly to society as a whole. Hyperbole has been added to certain sentences for literary and aesthetic effect. The point stands, however, that the IB is not for everyone and it should not be labelled as such. I acknowledge the value of the IB, this article is written simply to offer a counterpoint of synthesized student voices against the monolith that is the assemblies (and general portrayals) regarding the IB, which label it as an all-positive, all-enhancing curriculum.

On the Methodology¹:

Often, things like value judgements should not be used if writing Objective Journalism, which is true, but this is not the point. The built-in blind spots of the Objective rules and dogma frequently allow things to go uncriticized. The IB, for example, looks so good on paper that you could almost sign up for it without ever actually doing any research about it. To counter the blind-spot of the Objective and to see the Question of the IB clearly, it is necessary to get Subjective; and the shock of this recognition is often enlightening, perhaps more so than from Objective journalism. This is an opinion piece and should not be read as anything else.

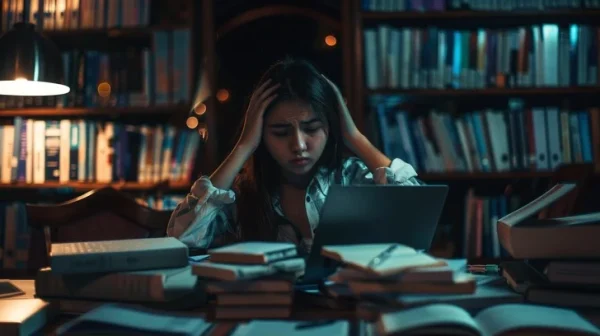

Final exams, as far as most students are concerned, have always been a metallic fence—the final border between nine months of agonizing torment and the freedom of summer. It is a rusty fence whose chainlinks clip away at our endurance, and the scars and scrapes of its barbed wire, if caught on skin, linger for the duration of the summer; rendering it unpleasant. The disappointment of having done badly on exams makes it seem as though your dreams of a pleasant future have just been triturated into nothingness. All hitherto fun activities, hobbies, and so on, seem now to be useless and pointless towards a successful academic future—for as we all know, that is what matters. Those who say otherwise, and attempt to place themselves outside of this scholastic ideology which holds academic strength as the key to life, disregard the fact that in the current stage of this world, as more and more people get college degrees, the importance of going to a good college increases. One cannot help but pessimistically wonder at a seemingly futile existence, working “temporary” jobs, being labeled as an “unskilled” worker, ending up like Gogol’s Akaky Akakievich, continuously alienated from the fruits of your labor while little-by-little becoming nothing more than a shell of skin and bones whose species-being is continuously denied—all because you did not do well in your exams. But it would be a mistake to say that the barbed wire lies on June 7th, for this would deny the spectre that haunts the soul—that constant nihilistic thought of an even more Sisyphean existence. It looms throughout the year, always hiding in the background, ready to pounce and crush the excitement of leaving school, as you are reminded that this is all in jeopardy.

A “7” is not simply a number: it is one step closer to a successful post-UNIS, post-IB life—something we all strive for. Getting a 7 is more than getting a good grade: it is a marker of excellence; a stamp of success. But the significance of a 7 is still clearly contingent upon its context—a 7 on a pop-quiz does not matter nearly as much as a 7 in the final exams of the IB. Although both may grant a degree of satisfaction — or lack thereof — the latter seems to have the potential to shape your life. Nothing, I imagine, is more painful than to have an inanimate, almost alien organization dictate the likely path of your life.

The IB’s gaze is a powerful one: students are now candidates, defined by numbers, not names. CAS is the closest thing at humanizing the candidate: it is aimed at “enhancing… personal and interpersonal development“; it is labelled as an “important counterbalance to the academic pressures of the DP”: it attempts to find the human in the figure. But even this fails: the candidate does CAS out of necessity. What is meant to be fun risks being turned into a monotonous, routine action stripped from any pleasure—its counter-hegemonic power (the hegemony in question being the association of success with academic productivity, not creativity), co-opted. It is also part of a contradiction. Being labelled as a counterpoint to the harsh academia of the DP, CAS does little more than to remove us from the studies we are so pressured to excel at. Thus, the IB, as composed of the DP and CAS, while being labelled as harmonious with the candidate, is little more than the excessive pressure of academic excellence and the failed anthropomorphism of figures through CAS. Automated grading, which was seen last year, only further strengthens the aforementioned points, (See Felipe Tavares’ article on model-based grading [and on its *expected* failure].)

Indeed, what constitutes the necessity for cumulative exams like the IB? Can it be the school’s necessity to establish academic legitimacy at the expense of the student’s well being? The intellectual narcissism of being able to say “All of our students participate in IB courses”? Or, is it a selfless act on behalf of the school that, out of a position of wisdom and experience, they impose on students because it will grant them well-being in the future?²

¹ Paraphrased and adapted from Dr. Hunter S. Thompson’s He Was a Crook (June 16, 1994)

² I do not mean to question administrative decisions of having exams; obviously they are necessary in the educational world we belong to.

Marta vilaca • Jun 16, 2021 at 02:20

Very interesting read.

Alica Barton • Jun 8, 2021 at 12:49

Very interesting!