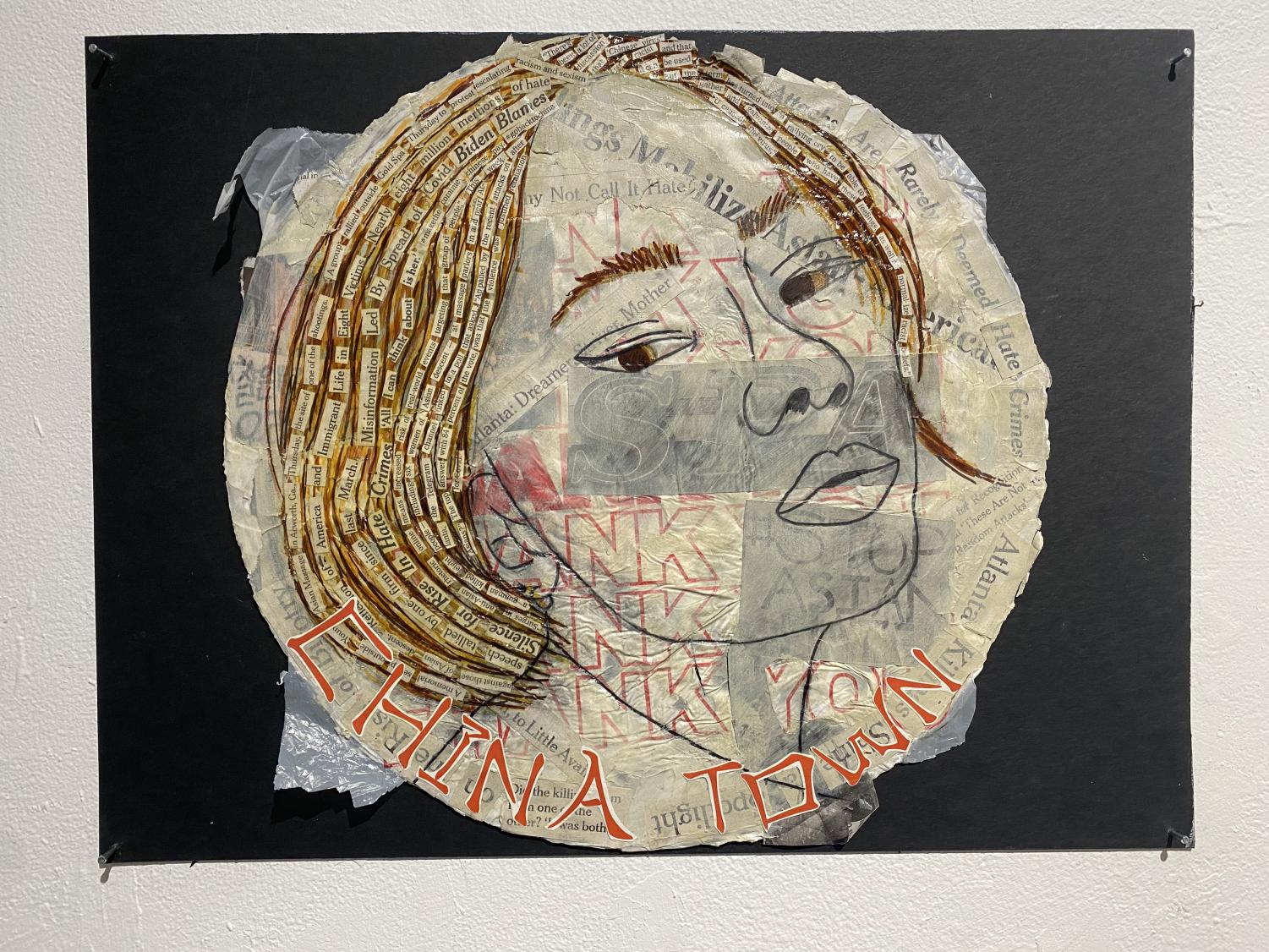

I am Here for You: Understanding AAPI Violence

April 28, 2021

As a young female Asian-American, this past year, I have been horrified at the violent attacks on Asian communities globally and violence against women that have come to the surface. I was adopted from Shanghai, China, when I was just under a year old by two loving American parents, and I have grown up in New York City. Once, when I was about ten waiting at the bus stop to go to school with my mom and sister, an older Asian man was slowly walking by, visibly glaring at the three of us. He slowly looked us up and down with his eyes and squinted in what felt like judgment and disappointment.

At this age, I was just beginning to understand that my family was considered “abnormal” by traditional societal standards. However, as I’ve grown up and learned more about my surroundings, I’ve realized that because I am of a different race than my parents, we are seen as different and unusual.

These kinds of incidents have continued to occur in my daily life. The other day, just as I had parted ways with my mom to go to Central Park to meet up with my friends, a man stopped me and said in a very demeaning tone, “I looooove Asian hair,” and walked away snickering to himself. A few days later, an Asian woman with two young Asian children walked past my mom and me –we had our arms linked as we walked down the street – and stared us up and down in a similar way to that man did when I was 10.

The constant staring was not the only micro-insult I experienced growing up. Starting around middle school, I began to get catcalled or whistled at on the streets and was called Asian slurs, like “chink” or “small-eyes.” This never bothered me much because I knew these were strangers that I would never see again. However, as I have grown older and learned more about my world and the dangerous implications of these kinds of snide comments, I realized how important it is for us to call people out — friends, family, and strangers alike — when they make discriminatory comments or insinuations. These hateful words could and have become somewhat normalized in modern society and have resulted in horrendous acts of violence, such as the Atlanta massacre and the increase in attacks on elderly Asian people around the United States and the world.

The night of the Atlanta shooting, I fell asleep crying, thinking about how I could become one of these headlines, “Young girl killed while walking her dog in Brooklyn”; I could become another statistic; a life lost because of someone’s pure hatred for me simply because of the color of my skin. The following morning, I woke up and checked my phone to see more and more GoFundMe pages for elderly AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islanders) people who had been beaten up or killed.

I woke up to see more informational graphics on Instagram about the Atlanta massacre, about an Asian man that was beaten and strangled unconscious on the subway, about a woman who was beaten by a man in San Francisco but was thankfully able to fight back.

I woke up to see friends and celebrities recounting their own traumatic stories about how they have been verbally or physically harassed on the street solely because of their race, the shape of their eyes, their supposedly “disgusting” culture, harmful stereotypes about them, and the pure hatred of terrible people in this world.

The headlines and personal anecdotes feel like they are never-ending, and although I appreciate my peers posting information about these kinds of attacks, it has become exhausting and frustrating to see these infographics every single time I open any social media app. I think all BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, people of color) and marginalized groups can relate to this sense of fatigue and constant anxiety that our lives could be taken simply because of our existence.

If you have ever felt like this, or do right now, I am here for you. I understand your pain and your fear. And I’m sorry you have felt or feel this way. We all deserve to live life without having to constantly be clutching our keys between our knuckles or having 911 on speed dial simply going to school or getting groceries.

I would also like to highlight that the Atlanta shooting and the various other reports of anti-Asian hate crimes are not a new phenomenon. We have been experiencing racism for a long time, but it has often been brushed under the rug because it’s “not as bad” as racism against other races and the false “model minority” trope. According to a report published by Stop AAPI Hate, nearly 3,800 incidents were reported over the last year throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. I think that anti-Asian hate has often been ignored because the “model minority” myth has been used to deem a minority group as more successful than other minority groups and is most often applied to Asian Americans, who are often praised for “apparent success across academic, economic, and cultural domains- successes typically offered in contrast to the perceived achievements of other racial groups” (The Practice). Tropes such as “all Asians are good at math” and “Asians are obedient and hardworking” undermine Asian American accomplishments, and create harmful stereotypes to those who may not fulfill them.

The model minority myth was intended to drive a wedge between Asian Americans and other disadvantaged groups in America. Yes, every minority group has suffered perhaps in more ways than others, but it’s not a competition of “who has it worst.” Minority groups and non-minority groups have to work together to stop all kinds of hate, discrimination, and exclusion of all types. When we are working with each other instead of against each other, it becomes more feasible to make actual lasting change that will benefit everyone in the end.

I hope that everyone takes some time to think about how they may or may not have contributed to normalizing microaggressions or any kind of hate. We need to hold each other and ourselves accountable because hatred can easily manifest itself into violence on somewhat rare occasions.

But honestly, aside from hoping and fighting for equality and against injustices and vicious race-based hate crimes, all I can wish for is for people to see me and families like my own for what they truly are: a whole REAL family that loves and cares for each other — not for our differences.

Kim • May 1, 2021 at 10:09

Thank you for sharing your experience and helping us become more aware of the impact of our actions.

Sadie S • Apr 30, 2021 at 10:59

Amazing work Sophie. So powerful.

Carole Sadler • Apr 30, 2021 at 10:53

Amazing Sophie. So well expressed and a valid message for us all. Kiki