A Primer on the Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict

Centuries of displacement and violence end in a tenuous peace deal.

January 27, 2021

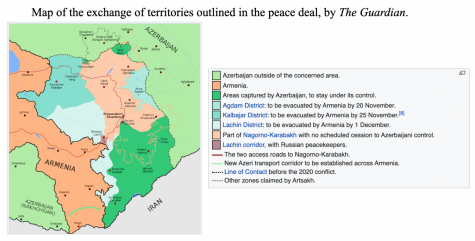

A map of the South Caucasus, right before the recent 2020 startup of conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh.

In the fall of last year, a war erupted between Armenia and Azerbaijan over a region called Nagorno-Karabakh. However, this conflict is by no means a new one, as the region has been contested between the two nations for the past decades. Both Armenia and Azerbaijan have foreign supporters, in a twisted network of international relations, causing the conflict to extend far outside the Caucasus, and even the Middle East. Despite a peace deal being signed by the combatants on November 9th, 2020, and the war coming to an end, the conflict between these two nations is by no means over. But why are Armenia and Azerbaijan fighting over Nagorno-Karabakh? What is the history behind this conflict? How has it made an impact on the global stage? And why is a permanent solution for peace so hard to achieve?

Background

From 1920 to 1991, Armenia and Azerbaijan were under the control of the Soviet Union, as separate SSRs (Soviet Socialist Republics). Their borders, including the region of Nagorno-Karabakh, were created and imposed on them by the Soviets, and they were drawn purposefully to cause conflict between the two ethnic groups. This was a common occurrence throughout the Soviet Union, in order to keep local populations focused on fighting each other rather than their Soviet rulers. As such, neither Armenia nor Azerbaijan were content with their shared border, but under Soviet control, the conflict was not able to break out into open war. For a more expansive and detailed history on the region of Nagorno-Karabakh and the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, click here.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, both states regained their independence, were led by nationalist governments, and claimed the region of Nagorno-Karabakh to be a part of their country. This region had a majority Armenian population, but did have a sizable Azeri minority, and was located in the middle of Azerbaijan. With their Soviet overlord now gone, there was nothing to prevent the outbreak of war between Armenia and Azerbaijan. There were attempts for a peace plan between the two countries, but they all failed, and distrust between the Armenians and Azeris grew.

The conflict escalated in 1992, when ethnic Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh declared independence from Azerbaijan. In the fighting that followed, tens of thousands of local Armenians and Azeris were killed, and a million people had to leave their homes. Both sides accused the other of committing atrocities, and civilians were rarely spared from the violence.

In 1994, Armenian forces successfully pushed Azerbaijan out of Nagorno-Karabakh, seized territories around it, and the two countries agreed to a ceasefire. The ethnic Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh established their own enclave, but soon took control of land that was populated by Azeris and historically a part of Azerbaijan. Armenians from outside the Caucasus were even brought in to settle in the former Azeri towns, and the Azeris in Nagorno-Karabakh were forced to leave. Although Armenia did not officially annex the region, Armenia was occupying and heavily supporting it.

The conflict over the region continued, and the ceasefire was ignored multiple times by both sides in the following years. The United Nations continued to recognize Nagorno-Karabakh as part of Azerbaijan’s territory, but it was effectively controlled by Armenia. The sense of injustice that occurred during the 1991-1994 war did not go away, and the countless killings and atrocities have sewn a deep line between Armenia and Azerbaijan. As such, the region as a whole became an absolute powder keg, vulnerable to an escalation at any time. After the ceasefire, the two nations hunkered down on either side of a line of control marked by landmines and snipers. However, there have been several attempts for peace before the 2020 escalation.

A map of the South Caucasus, right before the recent 2020 startup of conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh.

Recent Escalation of Conflict

In the Spring of 2020, an election organized by the self-declared Armenian government in Nagorno-Karabakh was viewed as a provocation in Azerbaijan and drew criticism from regional powers. In July, tensions started surging after a series of border clashes killed more than a dozen people, but the catalyst behind these clashes is still completely unknown. Both sides claim that the other attacked first. The fighting prompted thousands of Azeris to demonstrate for war with Armenia, and the skirmishes quickly escalated into a full-scale war, with trenches, tanks, artillery, rockets, and planes.

Azeri Forces have been attacking Nagorno-Karabakh’s main city, Stepanakert. Civilians are now forced to stay inside their basements to protect themselves from air attacks, and Armenian men in Stepanakert are signing up in large numbers to fight back. Armenian forces have been attacking Azerbaijan too, with the Azeri border city of Ganja being the hardest hit. Exact numbers of casualties are nearly impossible to obtain, but soldiers and civilians have been killed in the thousands. These attacks on cities behind the frontlines is another aspect of the recent fighting that separates it from the numerous border skirmishes before it. Both sides have begun rallying their people to fight, and full scale mobilization and martial law have been enacted.

It is possible that the border skirmishes were allowed to escalate into a full war because Azerbaijan now feels that it is capable of winning over Armenia, after years of the country building up its military and establishing foreign allies. This year’s round of border skirmishes might have just been the excuse they were looking for to finally reclaim Nagorno-Karabakh, and reverse the Azeri defeat in 1994. However, the Armenian government’s rhetoric has been equally as hawkish, and there is no evidence to definitively determine that either side instigated the war.

International Involvement

International intervention and participation have made this recent start-up of the conflict different from the many skirmishes before it. The most fervent intervention has been from Turkey, a long time staunch supporter of Azerbaijan. Turkey and Azerbaijan share close cultural ties, given their shared Turkic heritage. Ibrahim Kalin, the Turkish Presidential Spokesman, stated: “We call ourselves one nation, two states. What happens there is of course direct concern to us. It affects our borders, it affects our region.”

Opposingly, Turkey and Armenia have a long history of tensions. In 1993, Turkey closed its border with Armenia, and it has remained shut ever since. The two countries do not have diplomatic relations. In response to the recent conflict, Turkish President Erdoğan claimed, “We stand by our Azeri brothers in their fight to liberate their occupied lands and protect their homeland,” and he described Armenia as “the biggest threat to peace” in the region.

The degree to which Turkey is actually involved in the fighting is difficult to determine. Many of the military drones being used by Azerbaijan were supplied by Turkey, and Turkey has been accused of recruiting Syrian fighters to help against the Armenians, but both Turkey and Azerbaijan deny this. Turkey has made clear what its vision for an end to the conflict would be. “Our main concern is to find a diplomatic solution to this, but as I said, for this peace to be sustainable, it needs to be based on a plan to end the [Armenian] occupation [of Nagorno-Karabakh],” said Ibrahim Kalin.

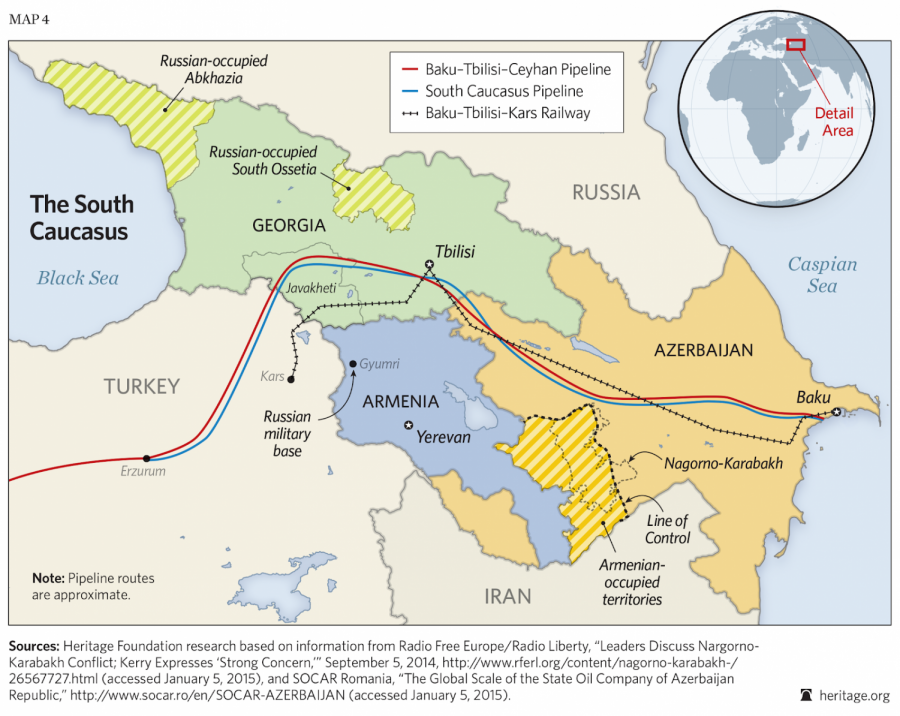

Russia plays a more ambiguous role in the region, as it has close economic ties to both Armenia and Azerbaijan, and supplies weapons to both. In an interview, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated: “…Russia has always had special ties with Armenia. But we have always had special relations with Azerbaijan too… For us, both Armenia and Azerbaijan are equal partners… Therefore, we take a position that would allow us to enjoy the trust of both one and the other side and play an essential role as mediators.” However, it should be noted that Armenia hosts a Russian military base, and is part of the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union. Also, Russia has a defence pact with Armenia that excludes any attacks on Nagorno-Karabakh, but if Azerbaijan advances into Armenia properly, then this defense pact could be called upon.

There are other countries involved, like Iran and Israel, which you can learn about here.

A Peace Treaty is Signed

After months of fighting, Azerbaijan successfully captured the strategically important town Shusha, finally prompting the two sides to agree to a ceasefire and peace deal on November 9, 2020. If you want to know why and how Azerbaijan won the war, click here.

The peace treaty was signed by Azeri President Ilham Aliyev, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, and Russian President Vladimir Putin. According to the agreement, Armenian forces are to withdraw from Armenian-occupied territories surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh, there will be an exchange of prisoners and the dead, and a Russian peacekeeping force of about 2,000 troops will be deployed to the region for a minimum of five years. Additionally, Armenia must guarantee the safety of passage between mainland Azerbaijan and its Nakhchivan exclave, via a strip of land in Armenia’s Syunik Province.

As of this writing, a large part of Nagorno-Karabakh still has no scheduled cession to Azerbaijan, due to the ethnic Armenian majority in the region, and the fact that it was not captured by Azeri forces. The fate of this piece of land remains unclear, but one task of the Russian peacekeeping force is to protect the link between Armenia proper and this piece of Nagorno-Karabakh, called the Lachin corridor.

The Reaction to these Terms

Following the announcement of a peace deal, violent protests erupted in the Armenian capital city of Yerevan, and there were chants of “We will not give it up.” Protesters broke into parliament and government buildings, beating up the speaker of the Parliament of Armenia, Ararat Mirzoyan, and even looted the prime minister’s official residence.

After signing the agreement, Prime Minister of Armenia Nikol Pashinyan claimed, “This is not a victory, but there is not defeat until you consider yourself defeated, we will never consider ourselves defeated and this shall become a new start of an era of our national unity and rebirth.” It is clear that although a peace deal has been signed, many Armenians do not accept defeat.

In the areas of Nagorno-Karabakh given to Azerbaijan, many Armenians living there are leaving, and seeking refuge in Armenia land. These now refugees simply do not trust Azerbaijan to rule over them, with some even burning their homes and land so as to not leave anything behind for the Azeris. The large degree of mistrust and hatred between the two peoples, grown over decades of conflict, has made itself evident.

Meanwhile in Baku, the capital city of Azerbaijan, large celebrations broke out, with cheers, singing, and lots of flag waving. The President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, reacted to the agreement by saying, “This statement constitutes Armenia’s capitulation. This statement puts an end to the years-long occupation.” The Azeris clearly see themselves as the victors.

In the United Nations, a spokesperson for Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, stated, “The Secretary-General is relieved that the deal has been agreed to on the cessation of hostilities. Our consistent focus has been on the well-being of civilians, on humanitarian access and on protecting lives, and we hope that this will now be achieved.”

Whether this peace treaty will last is still very much unknown. No amount of agreements will end the deep mistrust and anger between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Considering that the demands of these two nations are mutually exclusive, a permanent solution is nearly impossible to form.

What is known is that this war, and the conflicts before it, have caused incalculable suffering for both sides. In the thousands, family members and friends have been killed, homes destroyed, and spirits crushed. Considering what is at stake, the livelihood of these people, a long-lasting peace solution should not only be attempted, but strived to be achieved.

For a complete list of sources used in this article, click here.

Chloe • Feb 5, 2021 at 09:21

Thank you for this very enlightening article. The other thing I was wondering about is if the conflict has an cultural or religious component to it as well?